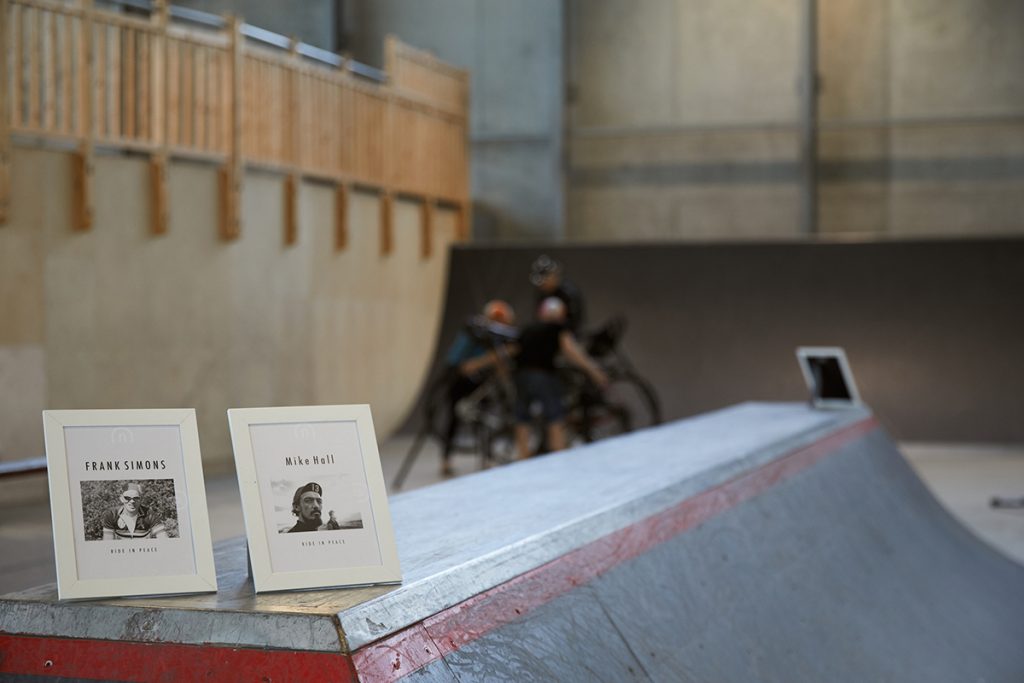

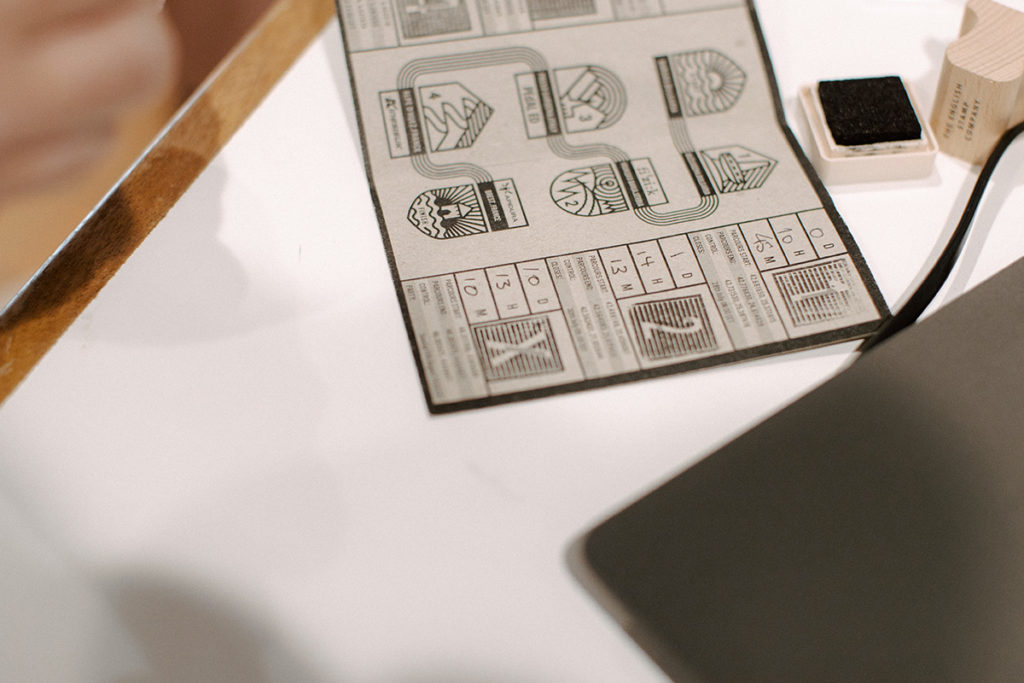

Days after setting out from Biarritz on Friday 4th October, its opulent casinos, the sweeping cliffs, late-season surf dudes and elegant cafés will be just a blur for the first riders who return at the end of the very first Trans Pyrenees self-supported ultra distance bike race. Instead, the luxurious start/finish location will become a scene of crumpled cyclists and dusty bikes, of broad grins of elation crossed with exhaustion, and immense pride tinged with relief. We are the proud main sponsors of the inaugural Trans Pyrenees Race: a 1500km test across some of Europe’s most beautiful yet brutal climbs. There will be thousands of meters of climbing and, like the more established Transcontinental Race – this summer’s seventh edition won sensationally by debutant Fiona Kolbinger – it’s a mixture of control points, some control parcours sections and the rest being whatever routes the riders choose to take though the most spectacular and remote scenery in the Pyrenees. The event is produced by Lost Dot, the team behind the Transcontinental Race, and based on a plan devised by the late Mike Hall. The familiar rules apply: with no external assistance allowed, the challenge of the riding itself is magnified by other demands including navigation, carrying kit, bike maintenance, lack of sleep, fueling, weather and more. There are 109 solo riders from right across Europe due to depart on Friday 4th, along with 14 set to ride in pairs from the Bay of Biscay on the west coast of France to the tip of the Cap de Creus peninsula in the Balearic Sea – on the Spanish side of the border, as much of the route will be – and back again. The fastest could finish in a long weekend, and the event stays open until Friday 11th October. All of them, just as Kolbinger and the other riders did in the Transcontinental Race, will have their brevet cards stamped at the control points which include the Spanish Pyrenean town of Ansó, on the Veral river; the Port de Cabús mountain pass on the Spain-Andorra border; and the Catalonian Cap de Creus headland. The return route is via the unforgiving cols: d’Aubisque, the Tourmalet and d’Aspin, following the route of the famous Le Raid Pyrénéen Randonneur. We’ll follow the riders’ progress via their GPS trackers and look forward to hearing about their adventures back in Biarritz. Photographs: Camille McMillan, Jonathan Hines

Fiona Kolbinger, the German 24-year-old bike racing debutante who led the seventh Transcontinental Race from before the halfway point, duly crossed the line as the winner at 07:34 on the morning of Tuesday, 6 August. It was a huge milestone moment for her and for the race. Not only did she win her first bike race in some style, but she’s also the first woman ever to win the TCR. There have been other women ultra-distance bike race winners but surely none with Fiona’s good humour, piano-playing prowess and all-round niceness. Although she made most of the race look easy, the final push was tough. Fiona seemed likely to beat the 10-day mark for the 3,500-kilometre race and was expected to arrive in the small hours of Tuesday morning. But in the end it took her 10 days, 2 hours and 48 minutes, after a final night she described as ‘too long, too dark and too grim.’ Coming from someone who smiled her way through the punishing parcours of the previous couple of weeks without complaint, that suggests some serious suffering. Despite the tough last push, Fiona’s margin of victory was relatively comfortable. Second-placed Ben Davies arrived just over 10 hours after she crossed the line, despite a valiant chase across France. Two hours later, Job Hendrickx came home in third place, and David Schuster looked certain to hold onto fourth. Behind them, the sharp end of a great cloud of following racers was gathering for the battle over minor positions. In this group was fizik ambassador Alex Jacobson, riding well in seventh place towards the end of the 11th day of the race, not far ahead of his fellow fizik riders Levy Bagoly and Matt Falconer. The last surviving fizik rider, Cento Bressan, was a few hundred kilometres further back, approaching the penultimate control point in the French Alps. Fiona found a winning formula and stuck to it. On her trusty Canyon Endurace fitted with a Aliante saddle, she cycled for 18-19 hours and then rested for five or six, every day, regardless of the weather or the hilliness of the route. And every day she ground out the miles, hour after hour, without fuss or complaint. As word spread of Fiona’s extraordinary achievement, more and more people started to take note. Dot-watchers appeared out of nowhere at control points, to take photos and cheer her on. Journalists turned up too, eager to find out who this phenomenal athlete was. As the end approached, the pressure of all this attention started to tell and the race organisers had to step in to protect the leader by issuing requests for restraint. Despite this, more than 30 people turned up to watch Fiona finish – at 7.30 on a Tuesday morning in an obscure youth hostel in Brittany. But there was no fanfare and little fuss when she finished. Just a quiet word of congratulation from one of the race organisers Rory Kemper, a quick stamp of the brevet card and then off to the hotel for a shower and some much-needed sleep. There’s little doubt that TCR founder Mike Hall would have approved.

After the relative calm of the Austrian Alps, the bustle of Le Bourg D’Oisans on market day feels almost overwhelming. Thousands of tourists amble through the town, pausing to refuel at patisseries and street cafés as they stroll between stalls selling everything from massive slabs of Gruyère to budget sports socks. This is a town that revolves around cycling. It sits in the shadow of the iconic Alpe d’Huez and within easy reach of many other famous cols, including the Croix de Fer, the Glandon, the Telegraphe and the magnificent Galibier. It’s the starting point of the infamous La Marmotte sportive ride – about which cyclists speak in hushed tones because of the savagery of the parcours, taking in just over 5,000 metres of climbing in 177km. La Marmotte might be tough, but the fourth parcours of the seventh Transcontinental Race is tougher, climbing just as much – up some of the same cols, in fact – but over 50 fewer kilometres. And let’s not forget that by the time the riders hit this parcours, they’ll have covered more than 2,500km with nowhere near enough sleep; they’ll be tired, sore and their bodies will be screaming at them to stop. But they’ll also know that this marks the end of the serious climbing in #TCRNo7. They’ll know that if they can just hold on for a few more days and pace themselves right for the 1,100km drag across France to the finish line in Brest, their race will be over. Race leader Fiona Kolbinger reached control point 4 on the terrace of the Hotel De Milan on the Rue Général de Gaulle just after 1pm on Saturday – around eight hours before second-placed Ben Davies. She looked as fit and fresh as anyone could possibly dare to hope they’d look after riding 2,500 gruelling kilometres in a week. After having her brevet card stamped, she shared the unexpected information that she sometimes sings to herself as she rides. During the TCR, she said, her favourite tunes were Highway to Hell and Staying Alive. She was feeling good, despite the 30+ degree heat. And this parcours had been her favourite so far. Then she popped into the hotel for some essential personal maintenance. But before disappearing, she sat down at the lobby piano and played a passable rendition of The Lion Sleeps Tonight – possibly the most surreal moment of the race so far. Behind Fiona, the race for third place is becoming intense. After an enforced pause at CP3, Sam Thomas lost his advantage, and now lags behind a group of riders that includes Job Hendrickx, Pawel Pulawski, David Schuster and Kosma Szafraniak among others. Not far behind them, three of the remaining fizik ambassadors – Alex Jacobson, Matt Falconer and Levy Bagoly – are all riding well, a few hundred kilometres ahead of the fourth, Cento Bressan. After the fourth control point, the parcours continues up the tough Col du Solude, a 12.5km climb with an average gradient of 7.5% with several sections steeper than 10%. It’s a prospect that Fiona dismissed with a shrug. “That’s not a hill – more of a hump.” After that the mountains are done with and it’s time for the long haul across France. The end of this epic race draws near. Fiona Kolbinger’s lead looks unassailable. But this is the Transcontinental – anything can happen.

In all the excitement about the savage off-road parcours leading to control point 2, it was easy to overlook what was coming next in the Transcontinental Race. The immediate challenge was to cross the 1,100km or so between southern Serbia and eastern Austria. Much of that long route is flat and relatively straightforward – if anything related to the Transcontinental can ever be described as straightforward. This is where the power-house riders settle into a big gear, hunker down on the aero bars and churn out the miles. The top riders aim to average 400km per day across the whole race, so they aim for daily totals up to 500km to compensate for days in the mountains when it’s all they can do to cover 200-250km. MORE CHALLENGING PARCOURS But if there’s one thing we’ve learned about the Transcontinental, it’s that the organisers don’t make things easy. To mark the race’s entry into the Alps, they added a 160km parcours section leading to the third control point at Pettneu am Arlberg. This 160km section features almost 5,000 metres of elevation, including some climbs that are as breath-taking to look at as they are to cycle up, including the stunning Timmelsjoch, the Passo Gardena and the climbs out of Barbiano and San Genesio. It’s a measure of race leader Fiona Kolbinger’s comfort in the hills that she reported no ill effects after this punishing parcours. She arrived at the third control point just after 1pm on day six of the race, looking as fresh as ever. There were no physical problems to report and no mechanical issues. She was surprised to be in the lead – but couldn’t see any reason why she wouldn’t hold onto it. This is a rider whose confidence is growing by the day. Not too far behind the leaders, the four surviving fizik ambassadors are all going well and seem in good spirits, although one of them, Levy Bagoly, had a tough first few days. He says: “I started to have really bad cramps, first in the left leg that was on pedalling duty, and then in the right one too. Advancing became almost impossible. But I forced my way to CP1. Once I got there I found out that I’d already fallen to 117th position. It was a bummer. I got down to Gabrovo and thought about scratching. But as Mike [Hall, Transcontinental founder] has underlined many times, you should never scratch in the night. So in the morning I decided to go on but not to force it. Ever since I’ve been feeling better and better and I’ve fought my way back into the top 20. It’s nice here so I’d like to stay.” DECISION TIME After control point three, the riders have a big decision to make. There are two obvious routes to the fourth control point at Alpe d’Huez in the French Alps: south through Italy or north through Switzerland. Which one riders choose could significantly shape the end of the race. Both routes are about the same length and include roughly the same amount of climbing. The Italian route might be perceived as the less challenging option – there’s a bit less up and down to contend with – but it also includes the relatively narrow, busy, poorly kept roads of the Po Valley, where things can also get blisteringly hot. The roads on the Swiss route are just more Swiss: smoother, broader and safer.

Fiona went north into Switzerland. Only time will tell if it was a wise choice. Whichever way the riders choose, at the end of the 600km leg lies yet another challenging parcours – featuring even more climbing than the last one. The TCR hasn’t finished dishing out the punishment just yet.

Björn Lenhard is a tough, understated guy. You don’t get to finish second, then third in the Transcontinental Race without being tough. So when he says something is unrideable, you can take him at his word. And that’s how he described parts of the third parcours in #TCRNo7, up and then back down the stunning Besna Kobila mountain in southern Serbia. The parcours includes a long section that’s euphemistically described as ‘gravel’ by the race organisers but that doesn’t really do it justice. It’s a steep and sketchy trail filled with fist-sized rocks sitting on loose sandy soil, beside fat gullies carved out by rain water streaming down the mountain. It’s the sort of terrain that would be challenging on a full-suspension mountain bike with fresh legs but on a fully-laden, skinny-tyred road bike? After 600km of riding? When the mind and body are already beyond tired? No thanks. Once this treacherous section of the parcours has been negotiated, there’s a 30km paved descent down Besna Kobila towards the second race control point at Inn Zormaris, where Transcontinental volunteers waited to stamp brevets and log times, incongruously surrounded by a Serbian wedding party of more than 200 people. Björn reached the fizik-sponsored control point a couple of hours ahead of anyone else, one day, nine hours and 17 minutes after the race started. Chugging down a large bottle of Coke, he patiently answered the questions that were fired at him. He’d had two and a half hours’ sleep since leaving Burgas. No punctures. No mechanicals. The heat was ‘crazy’. He’d been eating nothing but ‘TCR food’. And it was best not to ask about the makeshift padding on top of his saddle. Then, after a few minutes, he was off again, starting the long journey towards the third checkpoint in Austria. But before Jonathan Rankin, the second-placed rider, had arrived, Björn was back at the checkpoint and the untold story behind that makeshift padding was revealed. It involved a wasp sting and some abscesses and ultimately it led to a heart-breaking decision to scratch from the race. Of course, there were no complaints – – but the disappointment must have been acute for Björn. Meanwhile, other riders started to arrive at the control point. First Jonathan, then Kosma Szafranik, followed by Björn’s training partner Fiona Kolbinger. By the start of day three, Fiona had overtaken Jonathan to become the TCR’s first-ever woman race leader – although Kosma’s tracker had gone dark overnight so at the time of writing, organisers aren’t sure where he is. After checkpoint 2 comes the long haul up to the third checkpoint in Austria, more than 1000km away. The race continues – sadly without Björn.

The Sea Garden in Burgas on Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast, with its well-tended flower beds and broad promenades, seems a genteel spot for the start of something as brutal as the Transcontinental Race. During race registration, beside the striking Pantheon to the Fallen Antifascists monument, you must remind yourself from time to time that the happy-looking cyclists wandering around or lying on the grass chatting amiably are on the cusp of a truly remarkable feat of endurance. But a closer look reveals the tension that precedes any big bike ride – only more so. After all the preparation and the training and the route-mapping and the kit-checking and the bike-fettling, all these riders want to do is start riding. There’s a palpable collective nervousness in the air. Are we really doing this crazy thing? Because this isn’t just another big bike ride. This is a 4,000-kilometre race that will defeat a third of the riders as it winds its way through Bulgaria, up into the Serbian mountains and on towards the South Tirol, where Italy meets Austria, then heading west into the French Alps and then across the entirety of France, before finishing in Brest on the Atlantic coast. Driving towards Burgas in the soft early evening sunshine, it’s tempting to think that it might be a good idea to take part in the Transcontinental Race. For a hundred miles or more, there’s nothing but flat, lush countryside, filled with the colour of hundreds of sunflower fields. But on either side of this idyllic plain are distant mountain ranges. And it’s in the steep, narrow roads of these hills that the racers must start their epic journey across Europe. This being the Transcontinental, the organisers include some compulsory parcours that the riders must complete to qualify for the race. The start is one such a section. Just before 6am on Saturday, 27 July, the riders gathered once more in the Sea Garden. In the moments before an airhorn sent them on their way, bicycle bells rang out and scores of camera shutters clicked. Then, at last, they were on their way through the streets of Burgas, leaving behind just one poor soul wrestling with a flat tyre. What a start… Within minutes, riders’ friends and families, race organisers and TCR fans all over the world turned into dot-watchers, logging on to the race tracker at Trackleaders.com to check the progress of their riders and monitoring #TCRNo7 on social media.

We are happy to announce our partnership with the 2019 Transcontinental Race, starting July in Bulgaria, and the all-new Trans Pyrenees Race, starting at the Bay of Biscay in October! Transcontinental Race The Transcontinental Race is an ultra-distance endurance cycle race across Europe, competed every year by a select group of self-supported riders. It is widely regarded as one of the world’s toughest endurance cycle races. Competitors in the Transcontinental Race do not follow a set course for the entire route: there are fixed start and end points with mandatory control points along the way. All travel must be by bike and riders must work out their own optimum route between the controls, planning their own strategy of riding, sleeping and refueling, and carry all their own equipment such as clothing and spares – they can buy food and drink – along the way. The previous six editions have started in either the UK or Belgium to finish, anywhere between seven and ten days later, in Greece or Turkey. They have each featured between 3,000 and 4,000km distance with between 30,000 and 45,000m total ascent. The 2019 route is flipped, as the seventh edition starts in Burgas, Bulgaria on 26/27 July and runs East-West, to finish in Brest, France. Transcontinental and Trans Pyrenees Race are a tribute to the late Mike Hall, an exceptional endurance athlete and founder of the Transcontinental Race. Mike was involved in a fatal accident in March 2017 and it’s testament to his irrepressibly positive spirit that he remains a huge inspiration to the endurance racing community. Preparations for the 2019 will now start in earnest as the riders discover this week whether they have been successful in their applications to ride. Trans Pyrenees Race A new event created by Lost Dot, the organizers of The Transcontinental Race, is the Trans Pyrenees Race. Sharing the same principles as the original event, the first edition of the Trans Pyrenees Race – starting 4th October 2019 – is self-supported endurance riding over a shorter distance but with highly challenging climbing packed into its 1500km total distance. Its route will take participants from the Bay of Biscay through the beautiful yet punishing scenery of the Pyrenees to the Cap de Creus and back again.